I've always envied cartoonists. Not animators -- their frame-by-frame slaving sounds like a variation on that old childhood punishment of writing an apology over and over until the words become meaningful only as a carpal-tunnel ache -- but graphic novelists, comic book artists, whatever you want to call them. I loved newspaper comics as a kid, Calvin and Hobbes and the Far Side especially, as well as collections of one-panel wonders from The New Yorker magazine, the old ones by Thurber and Charles Addams. As an adult, I read comics less often than I used to; with the exception of Watchmen, I haven't tackled any of the big series in the superhero genre, and I only read a graphic novel every once in a long while. But the directness of the medium, the way it combines cinematic visual techniques with the one-on-one intimacy of an author's connection with a lone reader, still fascinates me.

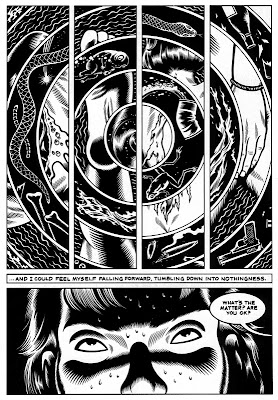

A few months ago, I read Black Hole by Charles Burns. I borrowed it from a friend, consumed it almost immediately, and then hung onto it for a long time, thinking I would write a blog post about it. Obviously I never did, and this post isn't primarily about it either. But today, thinking again about my ongoing discussion about difficulty, some of the images from that book sprang to mind.

Black Hole tells the story of a group of teenagers in the 1970's, beset with a mysterious STD that turns them into freaks: a girl sheds her skin, a boy develops a tiny talking mouth on his neck, and others contract maladies even more difficult to encapsulate in words. This is pulpy, suspenseful, and compelling in itself, and if Burns relied on the bare bones of the story to carry us through, I'd probably still have kept turning the pages. However, what he does is a lot stranger.

When reading the book, I was at first inclined to think that the disease the teens suffer from is meant to represent something from our world, most likely AIDS. But by the end, I became convinced that Burns is not working metaphorically, using one set of images to stand in for another set that the reader can supply. Black Hole, instead, is about the hidden connections between images: the way an incision in a frog's belly or a cut on the sole of a foot looks like a vagina, the way a tail resembles a penis. And as the book goes on, far from becoming easier to parse, these connections multiply. Objects -- bones, pipes, sandwiches, snakes -- stream across the pages, freed from their original context; panels break out from their orderly grid. We're no longer decoding symbols. The meaning of the objects clearly can't be divorced from the particular way they're depicted.

This is something we're more inclined to accept in visual art than in narrative. Perhaps it's because of the way literature is taught: at least at the places I attended, most American schoolchildren grew up thinking that it was possible to figure out what a poem "really meant," what a story was "about," and articulate this without the work's meaning being lost, as if literature were simply a foreign language they were learning to speak. Stylistic embellishments stood as obstacles in the way to understanding, an odd regional accent that made the speaker's words tougher to translate. "What is Wallace Stevens trying to say here?" one high school teacher said of the poem "Anecdote of the Jar," facing a classroom of dead silence. He sighed, deciding to give us a break. "All right, I'll just tell you: it's about environmentalism."

Yet, with visual art, the work qua object is not so easily dispensed with. Words can describe a painting or sculpture, but even a nine-year-old knows they cannot replace it. And thus, even if the technical aspects of the artwork -- the perspective, the composition, the colors -- are perceived to be unpleasant or disagreeable, difficult, they're still treated as part of the thing we're seeing, rather than something that prevents us from seeing that thing clearly.

Perhaps, though, the popularity of graphic novels (at least sophisticated ones like Black Hole) can serve as a bridge between these opposed ways of seeing visual art and narrative. Wouldn't that be nice?

Friday, September 24, 2010

Thursday, September 23, 2010

Send in the Clones

I am not a proponent of the faithful film adaptation. Many of my favorites (like Stanley Kubrick's Lolita or Terry Zwigoff's Ghostworld) veer wildly from their equally magnificent source material, and others (like Tim Burton's soul-consuming masterpiece Big Fish) actually improve upon the so-so books they tackle. To me, the important thing is not that a movie is true to the vision of the book upon which it's based; I only care that the movie is true to its own vision, that it creates, in its characters, settings, and story, something that takes advantage of the visual medium and creates a world unto itself.

However, when a film adaptation systematically skips over all of the incidents that made the novel original, poignant, and tenderly observed, when it drops out emotional complexity and internal conflict from its depictions of the characters, when it strips settings of their power and objects of their meaning, and when it neglects to replace any of these elements with anything, anything at all, besides horrible treacly predictable Hollywood schlock -- well, it's at those times that I wish I'd waited for the DVD. In his lovely and accomplished novel Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro describes a landscape through the eyes of the main characters, who have just, for the first time, left the boarding school where they grew up. "We could see hills in the distance that reminded us of the ones in the distance at Hailsham, but they seemed to us oddly crooked, like when you draw a picture of a friend and it's almost right but not quite, and the face on the sheet gives you the creeps," he writes. Mark Romanek's mediocre film adaptation of this very novel gave me a similar feeling, except that instead of "the creeps," one could more accurately say "the intense desire to cram Junior Mints in my ears to muffle the awful score."

To be fair, the movie isn't all bad. Romanek used to be a music video director (he also did the spooky Robin Williams vehicle One-Hour Photo), and he's decent at creating the film's visual world, which alternates in mood between a scruffy-preppy teen fall fashions photoshoot and the chilly operating rooms of Cronenberg's Dead Ringers. And the actors are all right, although in the later parts of the film, the exaggerated naivete and perpetually open mouth of leading man Andrew Garfield made me wonder if maybe his brain was in fact his first organ donation.

But the real problem here is the screenplay, a despicably shallow and mechanistic interpretation of the irreducibly complex relationships evoked by the book. After a 10 PM showing last night, I actually went home and reread over a hundred pages of Never Let Me Go, just to make sure I wasn't crazy for having liked it in the first place. I wasn't. One of the things the book excels at, above all else, is revealing the thorny and delicate nature of lifelong female friendships. The main character, Kathy H., and her best friend Ruth are close from the age of six or seven on, but this closeness isn't static: they draw close and pull apart, again and again, in a kind of dance. Superficially, Ruth is charismatic and social, more "popular" than her quieter friend, and there are moments when she holds this over Kathy. Yet Ruth is also intensely needy and vulnerable, desperate to be loved. Kathy understands this about Ruth in a way that no one else seems to; her attunement to Ruth's often minute internal fluctuations of mood make her irreplacable, but also provide her ample opportunities to call Ruth out on minor pretensions and casual half-truths. Neither girl is perfect, but their friendship with each other is precious, the defining tie of their childhoods and early adult lives.

The famous "Bechdel Test," taken from the comic strip "Dykes to Watch Out For," was derived from a panel where a character states she only will watch a film if it satisfies the following three requirements: it has to have at least two women in it, who talk to each other, about something besides a man. I think treating these components as prequisites is misguided and limiting -- many terrific movies feature only male characters, or only a man and a woman, or only a single woman navigating a male-dominated environment. However, I do think that this rule speaks to something that is regrettable about the way that female interaction is often depicted onscreen.

Case in point: in the stupid, stupid screenplay for Never Let Me Go, Ruth and Kathy's entire relationship is reduced to their mutual attraction to Tommy, a boy from Hailsham. Kathy loves Tommy. Ruth steals Tommy. Ruth gives Tommy back. The film turns Ruth into an evil man-eater and Kathy into a pathetic, sniveling victim. In this scenario, there is no reason for the girls to be friends, nothing between them except for barely concealed hostility, resentment, and competition. Yet the movie, for some reason, expects that viewers will invest in the girls' connection with each other -- that when they reunite, after ten years of separation, we'll care. Huh?

Moreover, this set-up reduces Tommy to an object, a pawn, entirely and inexplicably under Ruth's control. It's clear he and Kathy are sweethearts from day one; as small children, they exchange loving glances with such irritating frequency, it's like they're auditioning for an episode of the Wonder Years. But when Ruth decides she wants him, he takes her hand without hesitation. If the movie chalked this up to the fact it's Keira freaking Knightley, I'd believe he was just under the spell of an intense sexual attraction. But instead, it's weirdly apparent that he takes no pleasure from their love affair -- he even covers his eyes while they get it on, I guess to think of Kathy. So why is he with Ruth at all? I guess because he's a pathetic, sniveling victim too. He and Kathy really are soulmates... that is, if they have souls at all. I have to say that, by the end of the picture, I still wasn't entirely convinced.

Never Let Me Go is a science fiction story in that it has a speculative premise: these characters are being raised to donate their internal organs as adults. But even in the novel, this premise is the weakest part. I never really found it believable that the majority of ordinary people would accept the practice of raising clone children just to slaughter them for their livers and kidneys. I can't imagine what kind of science would necessitate the creation of full-fledged human donors with personalities rather than organs grown independently, or harvested from insentient bodies cultivated in farms. Even the widespread passivity of the donors is tough to swallow -- although I believe it about the students from Hailsham, whose misplaced loyalty to their alma mater keeps them from entirely turning their backs on the purpose for which they were raised.

Yet though I do think these logistical problems mar the novel, Ishiguro manages to deflect attention from them by keeping the focus on the personal, the everyday: the shades of meaning in an off-handed comment, the inside jokes and odd slang, the awkward hedonism of the characters' one night stands and communal porno collections. (As a sidenote, I think it's interesting how much sex Hollywood removed from this story. In the book, donors are unable to conceive children and thus are encouraged to enjoy casual sex for pleasure, even as young teenagers -- Kathy herself sleeps around compulsively. In the film, of course, she's treated as a repressed and saintly virgin, while smokin' hot Ruth stalks around post-coitally in a short robe: yet another way their friendship is dumbed down to fit catfight cliches.)

In other words, Kathy, as the book's narrator, is not concerned with the big picture of the world in which she lives; she's interested in the particularities of the people and places who have meant the most to her in her life, and she evokes these characters and settings so skillfully, so effortlessly, that it's tough not to feel like you've known them yourself.

In the movie, though, there is no such veil of minutia to shield us from the plot's gaping holes and so, at the very moments when we're meant to feel, we find ourselves thinking instead: about how the hell all of this could come to pass, about when it's going to end. Fortunately for us, if not for the characters, it's all over sooner than you'd expect.

However, when a film adaptation systematically skips over all of the incidents that made the novel original, poignant, and tenderly observed, when it drops out emotional complexity and internal conflict from its depictions of the characters, when it strips settings of their power and objects of their meaning, and when it neglects to replace any of these elements with anything, anything at all, besides horrible treacly predictable Hollywood schlock -- well, it's at those times that I wish I'd waited for the DVD. In his lovely and accomplished novel Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro describes a landscape through the eyes of the main characters, who have just, for the first time, left the boarding school where they grew up. "We could see hills in the distance that reminded us of the ones in the distance at Hailsham, but they seemed to us oddly crooked, like when you draw a picture of a friend and it's almost right but not quite, and the face on the sheet gives you the creeps," he writes. Mark Romanek's mediocre film adaptation of this very novel gave me a similar feeling, except that instead of "the creeps," one could more accurately say "the intense desire to cram Junior Mints in my ears to muffle the awful score."

Inside, I was screaming.

To be fair, the movie isn't all bad. Romanek used to be a music video director (he also did the spooky Robin Williams vehicle One-Hour Photo), and he's decent at creating the film's visual world, which alternates in mood between a scruffy-preppy teen fall fashions photoshoot and the chilly operating rooms of Cronenberg's Dead Ringers. And the actors are all right, although in the later parts of the film, the exaggerated naivete and perpetually open mouth of leading man Andrew Garfield made me wonder if maybe his brain was in fact his first organ donation.

But the real problem here is the screenplay, a despicably shallow and mechanistic interpretation of the irreducibly complex relationships evoked by the book. After a 10 PM showing last night, I actually went home and reread over a hundred pages of Never Let Me Go, just to make sure I wasn't crazy for having liked it in the first place. I wasn't. One of the things the book excels at, above all else, is revealing the thorny and delicate nature of lifelong female friendships. The main character, Kathy H., and her best friend Ruth are close from the age of six or seven on, but this closeness isn't static: they draw close and pull apart, again and again, in a kind of dance. Superficially, Ruth is charismatic and social, more "popular" than her quieter friend, and there are moments when she holds this over Kathy. Yet Ruth is also intensely needy and vulnerable, desperate to be loved. Kathy understands this about Ruth in a way that no one else seems to; her attunement to Ruth's often minute internal fluctuations of mood make her irreplacable, but also provide her ample opportunities to call Ruth out on minor pretensions and casual half-truths. Neither girl is perfect, but their friendship with each other is precious, the defining tie of their childhoods and early adult lives.

The famous "Bechdel Test," taken from the comic strip "Dykes to Watch Out For," was derived from a panel where a character states she only will watch a film if it satisfies the following three requirements: it has to have at least two women in it, who talk to each other, about something besides a man. I think treating these components as prequisites is misguided and limiting -- many terrific movies feature only male characters, or only a man and a woman, or only a single woman navigating a male-dominated environment. However, I do think that this rule speaks to something that is regrettable about the way that female interaction is often depicted onscreen.

Case in point: in the stupid, stupid screenplay for Never Let Me Go, Ruth and Kathy's entire relationship is reduced to their mutual attraction to Tommy, a boy from Hailsham. Kathy loves Tommy. Ruth steals Tommy. Ruth gives Tommy back. The film turns Ruth into an evil man-eater and Kathy into a pathetic, sniveling victim. In this scenario, there is no reason for the girls to be friends, nothing between them except for barely concealed hostility, resentment, and competition. Yet the movie, for some reason, expects that viewers will invest in the girls' connection with each other -- that when they reunite, after ten years of separation, we'll care. Huh?

Moreover, this set-up reduces Tommy to an object, a pawn, entirely and inexplicably under Ruth's control. It's clear he and Kathy are sweethearts from day one; as small children, they exchange loving glances with such irritating frequency, it's like they're auditioning for an episode of the Wonder Years. But when Ruth decides she wants him, he takes her hand without hesitation. If the movie chalked this up to the fact it's Keira freaking Knightley, I'd believe he was just under the spell of an intense sexual attraction. But instead, it's weirdly apparent that he takes no pleasure from their love affair -- he even covers his eyes while they get it on, I guess to think of Kathy. So why is he with Ruth at all? I guess because he's a pathetic, sniveling victim too. He and Kathy really are soulmates... that is, if they have souls at all. I have to say that, by the end of the picture, I still wasn't entirely convinced.

Never Let Me Go is a science fiction story in that it has a speculative premise: these characters are being raised to donate their internal organs as adults. But even in the novel, this premise is the weakest part. I never really found it believable that the majority of ordinary people would accept the practice of raising clone children just to slaughter them for their livers and kidneys. I can't imagine what kind of science would necessitate the creation of full-fledged human donors with personalities rather than organs grown independently, or harvested from insentient bodies cultivated in farms. Even the widespread passivity of the donors is tough to swallow -- although I believe it about the students from Hailsham, whose misplaced loyalty to their alma mater keeps them from entirely turning their backs on the purpose for which they were raised.

Yet though I do think these logistical problems mar the novel, Ishiguro manages to deflect attention from them by keeping the focus on the personal, the everyday: the shades of meaning in an off-handed comment, the inside jokes and odd slang, the awkward hedonism of the characters' one night stands and communal porno collections. (As a sidenote, I think it's interesting how much sex Hollywood removed from this story. In the book, donors are unable to conceive children and thus are encouraged to enjoy casual sex for pleasure, even as young teenagers -- Kathy herself sleeps around compulsively. In the film, of course, she's treated as a repressed and saintly virgin, while smokin' hot Ruth stalks around post-coitally in a short robe: yet another way their friendship is dumbed down to fit catfight cliches.)

In other words, Kathy, as the book's narrator, is not concerned with the big picture of the world in which she lives; she's interested in the particularities of the people and places who have meant the most to her in her life, and she evokes these characters and settings so skillfully, so effortlessly, that it's tough not to feel like you've known them yourself.

In the movie, though, there is no such veil of minutia to shield us from the plot's gaping holes and so, at the very moments when we're meant to feel, we find ourselves thinking instead: about how the hell all of this could come to pass, about when it's going to end. Fortunately for us, if not for the characters, it's all over sooner than you'd expect.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

Spoiled Rotten

A few weeks ago, I was lucky enough to finagle a free ticket to an advance screening of the hot new documentary film Catfish. I thought the movie was terrific and unsettling, but this post isn't primarily about that. This post is about the marketing strategy for that film, especially the tagline on its posters ("Don't Let Anyone Tell You What It Is"), and about the concept of spoilers in general.

As you may have noticed in my reviews of books and movies on here, I don't tend to shy away from talking about the twists or surprises of a story's plot (although I do give last-minute SPOILER ALERTs as a courtesy). To me, it seems impossible to discuss the work as a whole without making reference to the way it concludes, even/especially if that conclusion demands a reconsideration of the entire story that preceded it. Yet, as a viewer or reader myself, I do like to approach a narrative with as few preconceptions as possible -- not just about the ending, but in general. My own tendency to inflate my expectations for works made by my favorite writers or directors often amps up what would be moderate dissatisfaction to all-consuming anguish (Tim Burton, for the love of God, why?), and sometimes the early reviews or buzz surrounding a project will harden my heart against it, either out of writerly jealousy, that bitter green-eyed editorial assistant of the soul, or out of resentment toward what the author/director/story "represents" -- ignoring, of course, what the piece actually is. To me, the purest experience of new work would probably involve a blindfold, a mallet to the back of the head, and a rude awakening in a world where civilization creeps along atop the smoking ruins of mass media and the blogosphere. Until the Great Server Apocalypse claims us all, however, I tend to regard book and movie reviews as something best consumed after experiencing the work, when I'm desperate to join some sort of conversation with others who are wrestling with the same questions I am.

Back to Catfish, though. I don't think it's weird or bad that the filmmakers want to keep the story's conclusion veiled in secrecy: they're trying to draw in viewers through the sheer force of curiosity, one of the oldest tricks in showbiz (PT Barnum would surely approve). But there is something a little odd about the fact that commentators, whether or not they enjoyed the film, have adhered so closely to the creators' wishes -- especially considering that the meatiest and most reaction-provoking parts are in the last third or so, when the mystery rapidly unravels.

I'm not going to buck the trend and give away anything about the picture here, but I think it's fair to say that the movie is more of a character study than a horror story, and like any good character study, it thrives on detail and psychology, not on the lynchpin of any single incident or "reveal." And moreover, I think the makers of Catfish made it that way on purpose. Their footage (and the way they edited it) shows they weren't just after the one-two punch of their dramatic revelation. In fact, it's in those later parts that the film becomes the most impressionistic: I'm thinking in particular of a scene at the beach, and of the movie's title, which, far from being a coy hint, actually comes from a weird and poetic anecdote that relates to the story's action only metaphorically. All of this demands discussion, dissection, argument, yet none of that is happening in the public sphere. The filmmakers want to "get people talking" -- just not the people who have already seen the film.

The concept of spoilers comes, I think, from the idea that criticism is like a product review: that the reviewer's role is to tell potential readers or viewers what to buy. In this model, criticism is not so much a response as it is a preview: an advertisement or a warning label, depending. It's not a perspective that intrinsically values criticism as an art, one that should be whole and complete in itself. Instead it says that criticism must be good for something, for someone. It also puts an expiration date on reviews' cultural import, at least for films and books that become well-known enough to enter the popular consciousness. Imagine reading an essay about The Crying Game or The Sixth Sense that played coy with those films' third-act disclosures. Such an essay would seem almost aggressively irrelevant, not only revealing little about the films' own internal structures but also next to nothing about how or why their endings spoke to the public's obsessions -- like an article on the 2008 election that didn't mention who won.

Yet, when filmmakers or reviewers do divulge a story's secrets -- even if they're not so secret -- the public tends to rebel. I've been fascinated by this second phenomenon occurring with another film that just came out: the movie Never Let Me Go, based on the novel by Kazuo Ishiguro. I haven't seen the picture yet (I'm planning to go tonight), but I'm puzzled by the fact that so many folks, both online and in print, have flipped out about the alleged spoilers in the film's preview and pre-release coverage. Metro, the free NYC daily that my dog uses for toilet paper, even titled their review, "Never Watch the Trailer First." OK, I guess I should throw down a SPOILER ALERT of my own, but: really, guys? I haven't seen the movie yet, but in the book the supposed "shocker" is strongly implied even on the very first page. That "shocker" is in fact not a twist, but the premise: that the characters are clones who are going to be used for organ donations. Their understanding of this fact is riddled with denial and contradiction -- they wish it could be avoided, they sometimes picture other futures -- just as our own understanding that we will all die someday comes accompanied with many hopeful caveats. But they know, and the story that transpires in the book is in many ways concerned with that knowledge: with what it suggests about timidity, passivity, the desire to please authority, to conform at any cost, versus the forces of self-expression and love. The fact that people are responding so strongly to perceived spoilers where there are in fact none suggests to me something larger is at work here.

We live in a culture saturated with entertainment options. It isn't possible to read or watch everything, and it's completely understandable that people (including myself) want guidance on what to consume that does not completely forecast the work in advance. But I also think that informed, thoughtful, and comprehensive responses to narrative shouldn't dumb down or silence themselves. I'm not sure what the answer is. All I know is that Bruce Willis is a ghost.

As you may have noticed in my reviews of books and movies on here, I don't tend to shy away from talking about the twists or surprises of a story's plot (although I do give last-minute SPOILER ALERTs as a courtesy). To me, it seems impossible to discuss the work as a whole without making reference to the way it concludes, even/especially if that conclusion demands a reconsideration of the entire story that preceded it. Yet, as a viewer or reader myself, I do like to approach a narrative with as few preconceptions as possible -- not just about the ending, but in general. My own tendency to inflate my expectations for works made by my favorite writers or directors often amps up what would be moderate dissatisfaction to all-consuming anguish (Tim Burton, for the love of God, why?), and sometimes the early reviews or buzz surrounding a project will harden my heart against it, either out of writerly jealousy, that bitter green-eyed editorial assistant of the soul, or out of resentment toward what the author/director/story "represents" -- ignoring, of course, what the piece actually is. To me, the purest experience of new work would probably involve a blindfold, a mallet to the back of the head, and a rude awakening in a world where civilization creeps along atop the smoking ruins of mass media and the blogosphere. Until the Great Server Apocalypse claims us all, however, I tend to regard book and movie reviews as something best consumed after experiencing the work, when I'm desperate to join some sort of conversation with others who are wrestling with the same questions I am.

Back to Catfish, though. I don't think it's weird or bad that the filmmakers want to keep the story's conclusion veiled in secrecy: they're trying to draw in viewers through the sheer force of curiosity, one of the oldest tricks in showbiz (PT Barnum would surely approve). But there is something a little odd about the fact that commentators, whether or not they enjoyed the film, have adhered so closely to the creators' wishes -- especially considering that the meatiest and most reaction-provoking parts are in the last third or so, when the mystery rapidly unravels.

I'm not going to buck the trend and give away anything about the picture here, but I think it's fair to say that the movie is more of a character study than a horror story, and like any good character study, it thrives on detail and psychology, not on the lynchpin of any single incident or "reveal." And moreover, I think the makers of Catfish made it that way on purpose. Their footage (and the way they edited it) shows they weren't just after the one-two punch of their dramatic revelation. In fact, it's in those later parts that the film becomes the most impressionistic: I'm thinking in particular of a scene at the beach, and of the movie's title, which, far from being a coy hint, actually comes from a weird and poetic anecdote that relates to the story's action only metaphorically. All of this demands discussion, dissection, argument, yet none of that is happening in the public sphere. The filmmakers want to "get people talking" -- just not the people who have already seen the film.

The concept of spoilers comes, I think, from the idea that criticism is like a product review: that the reviewer's role is to tell potential readers or viewers what to buy. In this model, criticism is not so much a response as it is a preview: an advertisement or a warning label, depending. It's not a perspective that intrinsically values criticism as an art, one that should be whole and complete in itself. Instead it says that criticism must be good for something, for someone. It also puts an expiration date on reviews' cultural import, at least for films and books that become well-known enough to enter the popular consciousness. Imagine reading an essay about The Crying Game or The Sixth Sense that played coy with those films' third-act disclosures. Such an essay would seem almost aggressively irrelevant, not only revealing little about the films' own internal structures but also next to nothing about how or why their endings spoke to the public's obsessions -- like an article on the 2008 election that didn't mention who won.

Yet, when filmmakers or reviewers do divulge a story's secrets -- even if they're not so secret -- the public tends to rebel. I've been fascinated by this second phenomenon occurring with another film that just came out: the movie Never Let Me Go, based on the novel by Kazuo Ishiguro. I haven't seen the picture yet (I'm planning to go tonight), but I'm puzzled by the fact that so many folks, both online and in print, have flipped out about the alleged spoilers in the film's preview and pre-release coverage. Metro, the free NYC daily that my dog uses for toilet paper, even titled their review, "Never Watch the Trailer First." OK, I guess I should throw down a SPOILER ALERT of my own, but: really, guys? I haven't seen the movie yet, but in the book the supposed "shocker" is strongly implied even on the very first page. That "shocker" is in fact not a twist, but the premise: that the characters are clones who are going to be used for organ donations. Their understanding of this fact is riddled with denial and contradiction -- they wish it could be avoided, they sometimes picture other futures -- just as our own understanding that we will all die someday comes accompanied with many hopeful caveats. But they know, and the story that transpires in the book is in many ways concerned with that knowledge: with what it suggests about timidity, passivity, the desire to please authority, to conform at any cost, versus the forces of self-expression and love. The fact that people are responding so strongly to perceived spoilers where there are in fact none suggests to me something larger is at work here.

We live in a culture saturated with entertainment options. It isn't possible to read or watch everything, and it's completely understandable that people (including myself) want guidance on what to consume that does not completely forecast the work in advance. But I also think that informed, thoughtful, and comprehensive responses to narrative shouldn't dumb down or silence themselves. I'm not sure what the answer is. All I know is that Bruce Willis is a ghost.

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

I am a double agent for the KGB.

This is sort of cheating on my promise to post daily this week, but here goes: I've started writing (non-pseudonymous) book reviews for the KGB Bar Online Lit Journal, and my first one was just published to their site. So check it out! Here's the link:

http://kgbbar.com/lit/book_reviews/the_kasahara_school_of_nihilism

Monday, September 20, 2010

Degree of Difficulty, pt. 1

I've been complaining a lot lately about the way that we discuss -- or rather, don't discuss -- difficulty in fiction. To recap, it seems to me that the critical response to a "tough" or "inaccessible" book often falls into one of two categories: either the reviewer feigns comprehension, praising and criticizing so vaguely and so respectfully that calling him out on his confusion is nigh well impossible, or, perhaps even worse, the reviewer adheres to the Lev Grossman school of preemptive anti-intellectualism, declaring that the whole project of the novel or story collection in question is defunct, academic, "a drag," with no real regard for the specific approaches, techniques, and aesthetic of the work in question.

The problem with both of these approaches, in my opinion, is that they're motivated by something other than the writer's attempt to convey his own experience of a particular book. They are political, not in the sense of national party politics, but in the more general sense in which we might describe "office politics" at a company or "campus politics" at a college or university. The writer who pens, for example, exclusively positive reviews of experimental or avant-garde works is trying to pony up a readership, not so much for the book in question, but for other books of the same ilk, including, perhaps, his own; he also may hope to curry favor with other, more successful writers, meaning that the review is not, in fact, intended as a communication with other potential readers, but with the author of the book under review -- on the street, we call this "sucking up."

On the other hand, the anti-intellectual reviewer, while seeming to go on the offensive, actually is also playing defense, trying to protect the novelistic conventions (and pleasures) of yore from what he sees as an invading tribe of egg-headed marauders. Like the Fox News nutjobs who remind us every year that Christmas is under attack, these bozos seem to think that the works of Dickens and Austen (and Franzen and Updike) are in dire peril of being crowded off the shelves by the likes of Joy Williams and Gilbert Sorrentino. It's all a game of literary politics, and like any other form of politics, those politics cast every statement made under them in the seedy light of half-truth and overgeneralization.

Yet, what is it that actually makes a book difficult? And why are some kinds of perceived difficulty considered more impenetrable than others?

Perhaps the most extreme form of difficulty can be found in books that are difficult at the level of the sentence. The obvious example that springs to mind here is James Joyce, though he's not really an author I can handily cite. Confession time: I have never read Finnegan's Wake, and to be completely honest, it is likely that I will be nothing but a rotten smell behind a locked apartment door long before I ever attempt it. I have, however, opened it, and this is what greeted me within:

"riverrun, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodious vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs. Sir Tristram, violer d'amores, fr'over the short sea, had passen-core rearrived from North Armorica on this side the scraggy isthmus of Europe Minor to wielderfight his penisolate war: nor had topsawyer's rocks by the stream Oconee exaggerated themselse to Lauren's County gorgios while they went double their mumper all the time: nor avoice from afire bellowsed mishe mishe to tauftauf thuartpeatrick..."

This is the kind of prose that sends me reeling through the stacks in the direction of the T's, groping around for Thurber's collected works as an antidote. I don't claim this is a universal reaction. But what, exactly, makes it so off-putting to me?

I'd like to point out a couple of things that have occurred to me. The first is that, although I certainly don't know the meanings of all the words in the preceding passage, I don't think the issue is strictly one of vocabulary. As Lewis Carroll definitively proved in his wonderful poem "Jabberwocky," it's possible to have a piece of writing that thrives not on the reader's facility with the language used but simply with the context. Here's a brief passage from that poem that illustrates my point:

"He took his vorpal sword in hand: / Long time the manxome foe he sought – / So rested he by the Tumtum tree, / And stood awhile in thought. / And, as in uffish thought he stood, / The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame, / Came whiffling through the tulgey wood, / And burbled as it came!"

At least seven of the words in those eight short lines are nonsense words, words that literally no one could possibly understand. Yet Carroll does two things to keep the verse from becoming incomprehensible. The first is that he keeps the sentence structure simple. We're never perplexed about what part of speech a word is. It's especially clear to us who the two subjects of these sentences are – "he" and "the Jabberwock" – and the verbs Carroll uses are action verbs, placing these subjects in motion. This gives us the illusion that we can visualize the scene he's laying out, although we of course supply our own meaning to both "Jabberwock" and "whiffling" in the second sentence. The second thing Carroll does is place the "difficult" (i.e. nonsense) words mostly in what I'd describe as low-impact locations in the sentences. By this I mean that the difficult words are most often used as modifiers (specifically here, as adjectives, five out of seven times in this passage), which could be removed without significantly changing the sentence's meaning. For example:

"He took his sword in hand: / Long time the foe he sought – / So rested he by the tree, / And stood awhile in thought. / And, as in thought he stood..."

Though the modifiers are necessary aesthetically – the verse clearly would lose its unique sound, and the imaginative landscape it evokes, without them – they are not completely essential for meaning. (Sidenote: interestingly enough, the verse in the poem that uses the most nonsense words at high-impact points in the sentence ["Twas brillig, and the slithy toves..."] is even itself a kind of large-scale modifier, setting the scene just before and after the in-scene action takes place.) Thus, the reader can appreciate these words as decoration, embellishment, without relying on them for comprehension. These words function like the hippy chick friend who sees the world as poetry, who's moved almost to tears by the indoor rainbow that hangs in the air, however briefly, one afternoon in the mall when the fire alarm goes off and the ceiling sprinklers rain down unnecessarily. Having her there makes everything more beautiful, more meaningful, but you don't necessarily want to copy her notes from trigonometry class.

Yet in the passage I quoted from Finnegan's Wake, the sentence structure works against the reader's attempt to contextualize the unfamiliar words. The first sentence – or perhaps I should say mid-sentence – is in fact the more comprehensible of the two I quoted. The second sentence, in addition to its difficult language, immediately presents several grammatical challenges. For one thing, at least in American English, we're accustomed to "neither/nor" used in tandem as a conjunction. Since the sentence doesn't use a "neither," the "nor" that then appears immediately sent me looking back, assuming I'd missed something. For another, the sentence structure doesn't place the words that are (to me) difficult or incomprehensible at low-impact spots; it doesn't even make the parts of speech obvious (is "avoice" being used as a noun?).

I'm not saying any of this as a judgment, positive or negative, of the sentences in question, but merely as a statement of fact: the James Joyce sentences repel me, not primarily because they employ words that I don't recognize, but because they don't seem to anticipate my lack of recognition of those words. Opening Finnegan's Wake is like opening a novel and discovering it's in German: there's a sense in which I feel that this wasn't written for me.

Yet, there are times in my own experience as a reader when a work that was difficult at the level of the sentence did speak to me, even if that wasn't apparent at first. The obvious example of this, as I've noted before on this site, is the work of Thomas Pynchon. At the sentence level, Pynchon is, I think, a lot more easily parsable than late-period Joyce, but here's an example of a sentence from the opening section of Gravity's Rainbow that offers its own brand of WTF. Here, Pynchon starts describing one of Captain Geoffrey "Pirate" Prentice's famous banana breakfasts that he cooks for his men:

"Now there grows among all the rooms, replacing the night's old smoke, alcohol and sweat, the fragile, musaceous odor of Breakfast: flowery, permeating, surprising, more than the color of winter sunlight, taking over not so much through any brute pungency or volume as by the high intricacy to the weaving of its molecules, sharing the conjurer's secret by which – though it is not often Death is told so clearly to fuck off – the living genetic chains prove even labyrinthine enough to preserve some human face down ten or twenty generations... so the same assertion-through-structure allows this war morning's banana fragrance to meander, repossess, prevail."

Whew. What's puzzling in this sentence is different from what was puzzling the earlier examples: with the exception of a single word ("musaceous"), I'm familiar with all the vocabulary employed here. Even at the larger level of images, there's nothing evoked that I can't easily translate to a concrete visual. "Old smoke, alcohol and sweat," "winter sunlight," even "living genetic chains" are all perfectly clear, straightforward, and not particularly unfamiliar. Yet what confuses readers here – or at least what I found confusing upon first encountering it – is the rhetorical structure in which these component parts are placed. In comparing the scent of the banana breakfast with DNA, Pynchon is not trying to better or more clearly evoke the sensory experience of the breakfast. He skips from the level of description (which the reader anticipates at this junction) and goes straight to the level of themes, making a direct argument about the way an object's internal intricacy, its encoding, allows it to survive despite external threat.

This is a move that many traditional writers make – but at important moments, moments when the characters themselves might step back to observe the world around them with heightened clarity. Pynchon, though, just drops this in almost at random, in the middle of a scene establishing the men's daily routine. A lot of readers find this technique jarring and intrusive, and I can certainly see why. The effect of it – and several other sentences like it over the course of the book – is to create a world so densely riddled with rich veins of meaning that the present action often seems distant or absurd by comparison.

There are many, many other ways that fiction can be difficult at the level of the sentence. Another obvious one that springs to mind is when the book is written in the voice of a character or narrator whose dialect does not match the reader's: a classic case of "what's tough for me may be easy for you," and probably a secondary issue for American readers like me tackling Irish writers like Joyce. But I guess my main purpose here, rather than cataloging every variety of difficulty at the level of the sentence, is to point out the perhaps obvious fact that a writer's style is not merely a superficial element, a mannerism to be "gotten past."

Sentences are what a novel is made of, the air you have to breathe when you're inside the book. When sentences are difficult, I think that more than a book's length or subject matter or themes, they are the biggest impediment to the work reaching a broad audience. However, I also think that, if used purposefully, difficult sentences can allow writers to communicate ideas and images to their admittedly more limited audience that could not be expressed any other way. The question, in evaluating a work, shouldn't be, "Is this hard to read?" but "What makes this hard to read, and why?" Our desire to look past the language to the thing/world/character being conveyed is so strong, though, sometimes it makes this question tough to ask, let alone answer.

The problem with both of these approaches, in my opinion, is that they're motivated by something other than the writer's attempt to convey his own experience of a particular book. They are political, not in the sense of national party politics, but in the more general sense in which we might describe "office politics" at a company or "campus politics" at a college or university. The writer who pens, for example, exclusively positive reviews of experimental or avant-garde works is trying to pony up a readership, not so much for the book in question, but for other books of the same ilk, including, perhaps, his own; he also may hope to curry favor with other, more successful writers, meaning that the review is not, in fact, intended as a communication with other potential readers, but with the author of the book under review -- on the street, we call this "sucking up."

On the other hand, the anti-intellectual reviewer, while seeming to go on the offensive, actually is also playing defense, trying to protect the novelistic conventions (and pleasures) of yore from what he sees as an invading tribe of egg-headed marauders. Like the Fox News nutjobs who remind us every year that Christmas is under attack, these bozos seem to think that the works of Dickens and Austen (and Franzen and Updike) are in dire peril of being crowded off the shelves by the likes of Joy Williams and Gilbert Sorrentino. It's all a game of literary politics, and like any other form of politics, those politics cast every statement made under them in the seedy light of half-truth and overgeneralization.

Yet, what is it that actually makes a book difficult? And why are some kinds of perceived difficulty considered more impenetrable than others?

Perhaps the most extreme form of difficulty can be found in books that are difficult at the level of the sentence. The obvious example that springs to mind here is James Joyce, though he's not really an author I can handily cite. Confession time: I have never read Finnegan's Wake, and to be completely honest, it is likely that I will be nothing but a rotten smell behind a locked apartment door long before I ever attempt it. I have, however, opened it, and this is what greeted me within:

"riverrun, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodious vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs. Sir Tristram, violer d'amores, fr'over the short sea, had passen-core rearrived from North Armorica on this side the scraggy isthmus of Europe Minor to wielderfight his penisolate war: nor had topsawyer's rocks by the stream Oconee exaggerated themselse to Lauren's County gorgios while they went double their mumper all the time: nor avoice from afire bellowsed mishe mishe to tauftauf thuartpeatrick..."

This is the kind of prose that sends me reeling through the stacks in the direction of the T's, groping around for Thurber's collected works as an antidote. I don't claim this is a universal reaction. But what, exactly, makes it so off-putting to me?

I'll admit it: there are some things I'd rather not find on my bookshelf.

I'd like to point out a couple of things that have occurred to me. The first is that, although I certainly don't know the meanings of all the words in the preceding passage, I don't think the issue is strictly one of vocabulary. As Lewis Carroll definitively proved in his wonderful poem "Jabberwocky," it's possible to have a piece of writing that thrives not on the reader's facility with the language used but simply with the context. Here's a brief passage from that poem that illustrates my point:

"He took his vorpal sword in hand: / Long time the manxome foe he sought – / So rested he by the Tumtum tree, / And stood awhile in thought. / And, as in uffish thought he stood, / The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame, / Came whiffling through the tulgey wood, / And burbled as it came!"

At least seven of the words in those eight short lines are nonsense words, words that literally no one could possibly understand. Yet Carroll does two things to keep the verse from becoming incomprehensible. The first is that he keeps the sentence structure simple. We're never perplexed about what part of speech a word is. It's especially clear to us who the two subjects of these sentences are – "he" and "the Jabberwock" – and the verbs Carroll uses are action verbs, placing these subjects in motion. This gives us the illusion that we can visualize the scene he's laying out, although we of course supply our own meaning to both "Jabberwock" and "whiffling" in the second sentence. The second thing Carroll does is place the "difficult" (i.e. nonsense) words mostly in what I'd describe as low-impact locations in the sentences. By this I mean that the difficult words are most often used as modifiers (specifically here, as adjectives, five out of seven times in this passage), which could be removed without significantly changing the sentence's meaning. For example:

"He took his sword in hand: / Long time the foe he sought – / So rested he by the tree, / And stood awhile in thought. / And, as in thought he stood..."

Though the modifiers are necessary aesthetically – the verse clearly would lose its unique sound, and the imaginative landscape it evokes, without them – they are not completely essential for meaning. (Sidenote: interestingly enough, the verse in the poem that uses the most nonsense words at high-impact points in the sentence ["Twas brillig, and the slithy toves..."] is even itself a kind of large-scale modifier, setting the scene just before and after the in-scene action takes place.) Thus, the reader can appreciate these words as decoration, embellishment, without relying on them for comprehension. These words function like the hippy chick friend who sees the world as poetry, who's moved almost to tears by the indoor rainbow that hangs in the air, however briefly, one afternoon in the mall when the fire alarm goes off and the ceiling sprinklers rain down unnecessarily. Having her there makes everything more beautiful, more meaningful, but you don't necessarily want to copy her notes from trigonometry class.

Yet in the passage I quoted from Finnegan's Wake, the sentence structure works against the reader's attempt to contextualize the unfamiliar words. The first sentence – or perhaps I should say mid-sentence – is in fact the more comprehensible of the two I quoted. The second sentence, in addition to its difficult language, immediately presents several grammatical challenges. For one thing, at least in American English, we're accustomed to "neither/nor" used in tandem as a conjunction. Since the sentence doesn't use a "neither," the "nor" that then appears immediately sent me looking back, assuming I'd missed something. For another, the sentence structure doesn't place the words that are (to me) difficult or incomprehensible at low-impact spots; it doesn't even make the parts of speech obvious (is "avoice" being used as a noun?).

I'm not saying any of this as a judgment, positive or negative, of the sentences in question, but merely as a statement of fact: the James Joyce sentences repel me, not primarily because they employ words that I don't recognize, but because they don't seem to anticipate my lack of recognition of those words. Opening Finnegan's Wake is like opening a novel and discovering it's in German: there's a sense in which I feel that this wasn't written for me.

Yet, there are times in my own experience as a reader when a work that was difficult at the level of the sentence did speak to me, even if that wasn't apparent at first. The obvious example of this, as I've noted before on this site, is the work of Thomas Pynchon. At the sentence level, Pynchon is, I think, a lot more easily parsable than late-period Joyce, but here's an example of a sentence from the opening section of Gravity's Rainbow that offers its own brand of WTF. Here, Pynchon starts describing one of Captain Geoffrey "Pirate" Prentice's famous banana breakfasts that he cooks for his men:

"Now there grows among all the rooms, replacing the night's old smoke, alcohol and sweat, the fragile, musaceous odor of Breakfast: flowery, permeating, surprising, more than the color of winter sunlight, taking over not so much through any brute pungency or volume as by the high intricacy to the weaving of its molecules, sharing the conjurer's secret by which – though it is not often Death is told so clearly to fuck off – the living genetic chains prove even labyrinthine enough to preserve some human face down ten or twenty generations... so the same assertion-through-structure allows this war morning's banana fragrance to meander, repossess, prevail."

Whew. What's puzzling in this sentence is different from what was puzzling the earlier examples: with the exception of a single word ("musaceous"), I'm familiar with all the vocabulary employed here. Even at the larger level of images, there's nothing evoked that I can't easily translate to a concrete visual. "Old smoke, alcohol and sweat," "winter sunlight," even "living genetic chains" are all perfectly clear, straightforward, and not particularly unfamiliar. Yet what confuses readers here – or at least what I found confusing upon first encountering it – is the rhetorical structure in which these component parts are placed. In comparing the scent of the banana breakfast with DNA, Pynchon is not trying to better or more clearly evoke the sensory experience of the breakfast. He skips from the level of description (which the reader anticipates at this junction) and goes straight to the level of themes, making a direct argument about the way an object's internal intricacy, its encoding, allows it to survive despite external threat.

This is a move that many traditional writers make – but at important moments, moments when the characters themselves might step back to observe the world around them with heightened clarity. Pynchon, though, just drops this in almost at random, in the middle of a scene establishing the men's daily routine. A lot of readers find this technique jarring and intrusive, and I can certainly see why. The effect of it – and several other sentences like it over the course of the book – is to create a world so densely riddled with rich veins of meaning that the present action often seems distant or absurd by comparison.

There are many, many other ways that fiction can be difficult at the level of the sentence. Another obvious one that springs to mind is when the book is written in the voice of a character or narrator whose dialect does not match the reader's: a classic case of "what's tough for me may be easy for you," and probably a secondary issue for American readers like me tackling Irish writers like Joyce. But I guess my main purpose here, rather than cataloging every variety of difficulty at the level of the sentence, is to point out the perhaps obvious fact that a writer's style is not merely a superficial element, a mannerism to be "gotten past."

Sentences are what a novel is made of, the air you have to breathe when you're inside the book. When sentences are difficult, I think that more than a book's length or subject matter or themes, they are the biggest impediment to the work reaching a broad audience. However, I also think that, if used purposefully, difficult sentences can allow writers to communicate ideas and images to their admittedly more limited audience that could not be expressed any other way. The question, in evaluating a work, shouldn't be, "Is this hard to read?" but "What makes this hard to read, and why?" Our desire to look past the language to the thing/world/character being conveyed is so strong, though, sometimes it makes this question tough to ask, let alone answer.

Sunday, September 19, 2010

In the Haus

I do not fall in love easily. There are many authors I like and respect, many authors who have distinct voices, who competently and intelligently ply the tools of their craft. There are many other authors whose office chairs I wish came equipped with a remote-controlled emergency eject button, but that's the subject for another post. My point is that I am not easily bewitched. My first response to narrative is, generally, analytical, sober, even critical. I love to lose myself in the dream of fiction, but I usually know when I'm asleep, and when I awaken, I'm ready with an interpretation. A handful of times in my adult life, though, I've encountered authors who left me giddy, speechless, with little more than stammered profanity at my disposal to describe their work's impact on my ravished sensibilities. One of these authors I had the opportunity to see at the Brooklyn Book Festival last weekend, and the experience sent me tumbling head over heels all over again. I'm speaking, of course, of Steven Millhauser.

My love affair with Millhauser's work began when I was in college, when I mentioned to a professor that I was writing a series of slightly fantastical short stories about childhood, but intended for adult readers and with darkly adult themes. "You should check out Edwin Mullhouse," he suggested. "I'm not familiar with his work," I replied, feeling chronically underread; up until the previous day, I'd thought Evelyn Waugh was a woman. "Oh, no, Edwin Mullhouse isn't the writer -- well, he is, but he's fictional." "Wait, the writer is fictional? Like a pseudonym?" "No, no, the writer is Steven Millhauser." "So, wait, what's the title?" This who's-on-first went on for awhile, and I soon found myself in the library, searching for a book titled Steven Millhouse by Edwin Mullhauser. The pretension annoyed me -- in my opinion, only comedians on sitcoms were allowed to give their characters such close variations on their own names -- as did the nerve of this man, who back in the 1970's had already plagiarized what I thought was my own daring and original conceit: childhood recast as adulthood in uncanny miniature. Finally I found the book, and sitting on the floor between the shelves, flipped to the first page, eager to dismiss this pompous usurper, to parry his vision with a sharper one of my own. My professor had compared him to Nabokov, but, I reminded myself, one imitated Nabokov at his own peril; one always forgot the visual, the only weapon keen enough to cut loose from those brambles of language. I read, "I met Jeffrey Cartwright in the sixth grade... I can remember nothing physical about him except his tremendous eyeglasses, which seemed to conceal his eyes; somewhere in the dark attic of memory I have preserved an image of him turning his head and revealing two round lenses aglow with light, the eyes invisible, as if he were some fabulous creature who lived in a cave or well." I murmured to myself, "Oh fucking kill me now." Millhauser was the fabulous creature, possessed of dark and unholy powers, and by the end of the first paragraph, I'd handed him my bloody and still-beating heart.

Before Edwin Mullhouse, I had never understood the urge, possessed by characters in Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, to memorize a book in its entirety. I loved Pynchon's prose, but it was to me then as towering and mysterious as scripture, something from another realm. The sentences in Edwin Mullhouse, on the other hand, were ordinary things, bejeweled with precision. I fell in love with them individually, reading them aloud, out of context, to anyone who would listen. Describing a mischevious little girl, Millhauser wrote, "Her favorite dress was a short bright red one with puffed short sleeves, from which her short solid arms hung down alertly, as if she were perpetually prepared to snatch your crayons." Describing Edwin Mullhouse's grandmother visiting, he wrote, "After the first day, when she talked to Mr. and Mrs. Mullhouse about arthritis, rheumatism, and rising prices, Grandma Mullhouse spent all her time with Edwin... playing Go Fish and Old Maid, making vast bowls of custard or huge yellow cakes with orange icing, and telling stories about the man who thought she was thirty-eight or the man who thought she was thirty-five or the time she used to give piano lessons before her fingers got crooked or the time she was thrown from a merry-go-round halfway across the park and landed on her back and stood up without a scratch; it would have killed most people." Of a winter day chez Mullhouse, he wrote, "On the shady side of the house the icicles hung hard and frozen, but they were less lovely than the sunny icicles, shining with dissolution." His ability to specify tiny details that most people wouldn't even have noticed, to wrap an entire character or stage of life into a list, seemed sorcerous not because it came out of nowhere; to the contrary, the very familiarity of his materials was what made his sleight-of-hand dazzle me. Once when I was a small child, a birthday party magician put a rubber clown nose on his face and squeaked it; he then pinched my own ordinary nose and made it squeak too. Edwin Mullhouse released the magic power from everyday things in much the same way.

I did not read any more Millhauser for a long time after that. I was afraid, on one hand, of him disappointing me, and on the other hand, of him not disappointing me enough. I'd never before encountered an author so capable of influencing my writing style, drawing me, line by line, under his spell. Though the titles of his other books enticed me, some part of me wanted to resist. I held off until one day when, during the following summer and on vacation with my parents, I received a call from my boyfriend. He'd tried to check Edwin Mullhouse out from the library, but they hadn't had it in stock; instead he'd gotten a story collection called The Knife Thrower. "You have to read it," he said.

I read it, and then I read it again, and then I read everything else Millhauser has ever published. It's all terrific, but The Knife Thrower might actually be Millhauser's masterpiece. It's twelve stories and with the possible exception of one ("The Way Out") every single piece is a skull-melting, life-altering volcanic eruption of sheer literary force. Millhauser is obsessed with escalation, the way that, inch by inch, an artist's mind or a community succumbs to its own excesses. In The Knife Thrower, three separate characters vanish, or nearly vanish, into the sky's gulping blue ("Flying Carpets," "Claire de Lune," "Balloon Flight, 1870"); ordinary settings, like a department store or a suburban town past dark, open into deeper and deeper chambers within themselves, becoming self-enclosed worlds, unknowable from the outside. But the stand-out piece in the collection -- if such a thing can exist in a collection that left me so overwhelmed with pleasure I frequently forgot to breathe between paragraphs -- is the modestly titled "A Visit," an understated short story that achingly reveals the uncharted loneliness of so much of adult life, as well as the unsolvable riddle of romantic love: that's all I'll say about it here.

Millhauser read from The Knife Thrower at the Brooklyn Book Festival last Sunday, from a passage in his story "Paradise Park." The story concerns a Coney Island amusement park that, over time, develops from a family-friendly day trip destination into something straight out of the mind of Hieronymus Bosch. In the passage Millhauser read, about a level in the many-tiered pleasure playground nicknamed "Devil's Park," he described children dressed as concubines, a lover's leap that serves as the site of multiple suicides, and a roller coaster that plunges to its destruction again and again in a dark field.

The other panelists looked on, aghast and admiring, respectively; the mood of the audience, like the moods of the audiences in so many of his pieces, was awestruck and more than a little unsettled: his words whizzed by our ears too close, like so many coldly glittering daggers. But as much as I loved the piece, what I loved more was something he said during the Q&A session that followed. When asked by the moderator if there's ever a time when he's gone "too far" in his writing, Millhauser thought for a moment and then responded that he sees fiction as a seduction, a gradual casting-off of veils. There's no such thing as "too far," only "too soon."

This statement encapsulated perfectly what it is I love most about Millhauser's writing. His prose is decadent, forever reaching toward voluptuous release -- but what makes it truly compelling is his restraint. Perhaps the reason I so love his work is that, in the tenderness and care it takes in presenting each image, each rhetorical turn, it seems to love me back.

My love affair with Millhauser's work began when I was in college, when I mentioned to a professor that I was writing a series of slightly fantastical short stories about childhood, but intended for adult readers and with darkly adult themes. "You should check out Edwin Mullhouse," he suggested. "I'm not familiar with his work," I replied, feeling chronically underread; up until the previous day, I'd thought Evelyn Waugh was a woman. "Oh, no, Edwin Mullhouse isn't the writer -- well, he is, but he's fictional." "Wait, the writer is fictional? Like a pseudonym?" "No, no, the writer is Steven Millhauser." "So, wait, what's the title?" This who's-on-first went on for awhile, and I soon found myself in the library, searching for a book titled Steven Millhouse by Edwin Mullhauser. The pretension annoyed me -- in my opinion, only comedians on sitcoms were allowed to give their characters such close variations on their own names -- as did the nerve of this man, who back in the 1970's had already plagiarized what I thought was my own daring and original conceit: childhood recast as adulthood in uncanny miniature. Finally I found the book, and sitting on the floor between the shelves, flipped to the first page, eager to dismiss this pompous usurper, to parry his vision with a sharper one of my own. My professor had compared him to Nabokov, but, I reminded myself, one imitated Nabokov at his own peril; one always forgot the visual, the only weapon keen enough to cut loose from those brambles of language. I read, "I met Jeffrey Cartwright in the sixth grade... I can remember nothing physical about him except his tremendous eyeglasses, which seemed to conceal his eyes; somewhere in the dark attic of memory I have preserved an image of him turning his head and revealing two round lenses aglow with light, the eyes invisible, as if he were some fabulous creature who lived in a cave or well." I murmured to myself, "Oh fucking kill me now." Millhauser was the fabulous creature, possessed of dark and unholy powers, and by the end of the first paragraph, I'd handed him my bloody and still-beating heart.

Before Edwin Mullhouse, I had never understood the urge, possessed by characters in Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, to memorize a book in its entirety. I loved Pynchon's prose, but it was to me then as towering and mysterious as scripture, something from another realm. The sentences in Edwin Mullhouse, on the other hand, were ordinary things, bejeweled with precision. I fell in love with them individually, reading them aloud, out of context, to anyone who would listen. Describing a mischevious little girl, Millhauser wrote, "Her favorite dress was a short bright red one with puffed short sleeves, from which her short solid arms hung down alertly, as if she were perpetually prepared to snatch your crayons." Describing Edwin Mullhouse's grandmother visiting, he wrote, "After the first day, when she talked to Mr. and Mrs. Mullhouse about arthritis, rheumatism, and rising prices, Grandma Mullhouse spent all her time with Edwin... playing Go Fish and Old Maid, making vast bowls of custard or huge yellow cakes with orange icing, and telling stories about the man who thought she was thirty-eight or the man who thought she was thirty-five or the time she used to give piano lessons before her fingers got crooked or the time she was thrown from a merry-go-round halfway across the park and landed on her back and stood up without a scratch; it would have killed most people." Of a winter day chez Mullhouse, he wrote, "On the shady side of the house the icicles hung hard and frozen, but they were less lovely than the sunny icicles, shining with dissolution." His ability to specify tiny details that most people wouldn't even have noticed, to wrap an entire character or stage of life into a list, seemed sorcerous not because it came out of nowhere; to the contrary, the very familiarity of his materials was what made his sleight-of-hand dazzle me. Once when I was a small child, a birthday party magician put a rubber clown nose on his face and squeaked it; he then pinched my own ordinary nose and made it squeak too. Edwin Mullhouse released the magic power from everyday things in much the same way.

I did not read any more Millhauser for a long time after that. I was afraid, on one hand, of him disappointing me, and on the other hand, of him not disappointing me enough. I'd never before encountered an author so capable of influencing my writing style, drawing me, line by line, under his spell. Though the titles of his other books enticed me, some part of me wanted to resist. I held off until one day when, during the following summer and on vacation with my parents, I received a call from my boyfriend. He'd tried to check Edwin Mullhouse out from the library, but they hadn't had it in stock; instead he'd gotten a story collection called The Knife Thrower. "You have to read it," he said.

I read it, and then I read it again, and then I read everything else Millhauser has ever published. It's all terrific, but The Knife Thrower might actually be Millhauser's masterpiece. It's twelve stories and with the possible exception of one ("The Way Out") every single piece is a skull-melting, life-altering volcanic eruption of sheer literary force. Millhauser is obsessed with escalation, the way that, inch by inch, an artist's mind or a community succumbs to its own excesses. In The Knife Thrower, three separate characters vanish, or nearly vanish, into the sky's gulping blue ("Flying Carpets," "Claire de Lune," "Balloon Flight, 1870"); ordinary settings, like a department store or a suburban town past dark, open into deeper and deeper chambers within themselves, becoming self-enclosed worlds, unknowable from the outside. But the stand-out piece in the collection -- if such a thing can exist in a collection that left me so overwhelmed with pleasure I frequently forgot to breathe between paragraphs -- is the modestly titled "A Visit," an understated short story that achingly reveals the uncharted loneliness of so much of adult life, as well as the unsolvable riddle of romantic love: that's all I'll say about it here.

Millhauser read from The Knife Thrower at the Brooklyn Book Festival last Sunday, from a passage in his story "Paradise Park." The story concerns a Coney Island amusement park that, over time, develops from a family-friendly day trip destination into something straight out of the mind of Hieronymus Bosch. In the passage Millhauser read, about a level in the many-tiered pleasure playground nicknamed "Devil's Park," he described children dressed as concubines, a lover's leap that serves as the site of multiple suicides, and a roller coaster that plunges to its destruction again and again in a dark field.

Welcome to the pleasure dome.

This statement encapsulated perfectly what it is I love most about Millhauser's writing. His prose is decadent, forever reaching toward voluptuous release -- but what makes it truly compelling is his restraint. Perhaps the reason I so love his work is that, in the tenderness and care it takes in presenting each image, each rhetorical turn, it seems to love me back.

Saturday, September 18, 2010

Clowning Around

Sometimes I think I was born in the wrong era: I was meant for a time when words were chiseled in stone. As I've mentioned in previous posts, blogging does not come naturally to me. Despite my mantra of quantity over quality, my neurotic tendency toward perfectionism tends to keep me from posting early and often, and when I do blog, the two or so hours following the new piece's first appearance on the site are usually filled with partial rereadings and the micro-panics they induce (Jesus Christ, I used the same verb in two sentences! What is up with all these dashes, this shit reads like Morse code!). The sentences I write haunt me, replay in my head, like the weird pronouncements of a schizophrenic's dog. I need to get them right, or they'll never leave me alone. In a discussion about his novel Motherless Brooklyn, which features a narrator with Tourettes, Jonathan Lethem once described his revision process as itself Tourettic, a "compulsive grooming" of language, and while my results are nowhere near as well-coiffed as his, I have to say the description resonates with me.

It will probably not surprise many of my readers to learn that I'm working on a novel -- or, perhaps more accurately, that I am working on working on a novel. This is not my first book. I wrote a novel before when I was in graduate school: a bildungsroman, unsurprisingly, about a naive clown who can only understand his life and the people around him through the zany antics of his art. I wish I could say that the book was universally reviled, but even that wouldn't be accurate. Imagine if, at the end of the Lord of the Rings series, after all their trials and adventures, Frodo & Co. threw the magic jewelry into the Cracks of Doom, only to receive no reaction whatsoever. Imagine now that instead of a hobbit, he's a pretentious Manhattanite in velvet overalls and pirate boots and that the ring is an MFA thesis. Now you're beginning to understand my pain.

Probably because I've been burned before by the molten lava of rejection, I am writing my new novel even more slowly than I write my posts for this blog. And it's nearly impossible for me to work on both simultaneously. Which I find incredibly frustrating, because I need both outlets, both forms of communication. For periods of time in the past, I've abandoned the novel, but going without writing fiction makes me feel trapped, claustrophobic in the narrow confines of reality. Yet since I started blogging, responding to books and film and ideas in writing has become essential for me too -- it's as though I don't know precisely what I think until I work it out in prose.

I promised last month that I was going to try to write more on here -- that, like the pencil sculptor, I would adopt the credo, "This will break eventually but let's see how far I get." Then I disappeared from the blog for nearly three weeks, a fact probably unnoticed by most everyone but me, but which I regard as a personal failing nonetheless. So here's what I'm going to do: starting today, I am going to blog something every day for one week. Some of the posts will be stupid. Most of them will be short. But all of them will be available online, for your perusal and entertainment.

It will probably not surprise many of my readers to learn that I'm working on a novel -- or, perhaps more accurately, that I am working on working on a novel. This is not my first book. I wrote a novel before when I was in graduate school: a bildungsroman, unsurprisingly, about a naive clown who can only understand his life and the people around him through the zany antics of his art. I wish I could say that the book was universally reviled, but even that wouldn't be accurate. Imagine if, at the end of the Lord of the Rings series, after all their trials and adventures, Frodo & Co. threw the magic jewelry into the Cracks of Doom, only to receive no reaction whatsoever. Imagine now that instead of a hobbit, he's a pretentious Manhattanite in velvet overalls and pirate boots and that the ring is an MFA thesis. Now you're beginning to understand my pain.

The tears of a clown.

Probably because I've been burned before by the molten lava of rejection, I am writing my new novel even more slowly than I write my posts for this blog. And it's nearly impossible for me to work on both simultaneously. Which I find incredibly frustrating, because I need both outlets, both forms of communication. For periods of time in the past, I've abandoned the novel, but going without writing fiction makes me feel trapped, claustrophobic in the narrow confines of reality. Yet since I started blogging, responding to books and film and ideas in writing has become essential for me too -- it's as though I don't know precisely what I think until I work it out in prose.